Surprisingly, no! A quark is not the smallest particle of an element. Electrons still hold that title.

What is an element?

An element is a collection of protons, neutrons, and electrons, which has certain chemical and physical properties. If you reduce some pure mass to a single atom, that atom will still have those physical and chemical properties.

You can separate that atom into its component protons, neutrons, and electrons. These individual components will no longer have those chemical and physical properties. An atom is the smallest unit at which a combination of particles are still an element. If you divide them further, you no longer have an element.

Notably, atoms interact with light in unique ways. Roughly analogous to the way that a prism bends light, an atom—a system of smaller particles—interact with light that passes through that system of particle.

Hydrogen, for example, contains an electron which whizzes around, enveloping a proton. When light (electromagnetic waves) tickle that electron, it might make the electron—relative to the proton—more energetic. And if this electron loses this energy, it will then re-emit light of a specific, predictable energy.

Astronomers on Earth know what stars are made from many millions of light years away because of these lines. This is also—similarly—why putting certain metals in certain fireworks causes certain colors.

What are the smallest particles an atom is made of?

However, if you were to “un-bind” these protons and electrons (and neutrons), these properties would completely disappear.

For reasons, nature has decided that protons, electrons, and neutrons are likely to bind together in a relatively stable system of particles. (But that pesky neutron likes to keep things interesting!)

So, an element is just a label we give for a common, collection of particles—proton, electron, neutron—that we see frequently. And we know that when we see two atoms which are the same element, they will have identical chemical properties.

In fact, if you put two atoms of them same element (with the same number of neutrons) near each other—they are so identical—you have no way to tell them apart. So giving them a specific name is a pretty good idea.

But wait, so aren’t quarks the smallest part of an element? This is a tough question. It helps to look at the basic particles in the Standard Model.

But, you won’t find a proton and neutron on this table because they are not fundamental particles. They are hadrons–combinations of quarks.

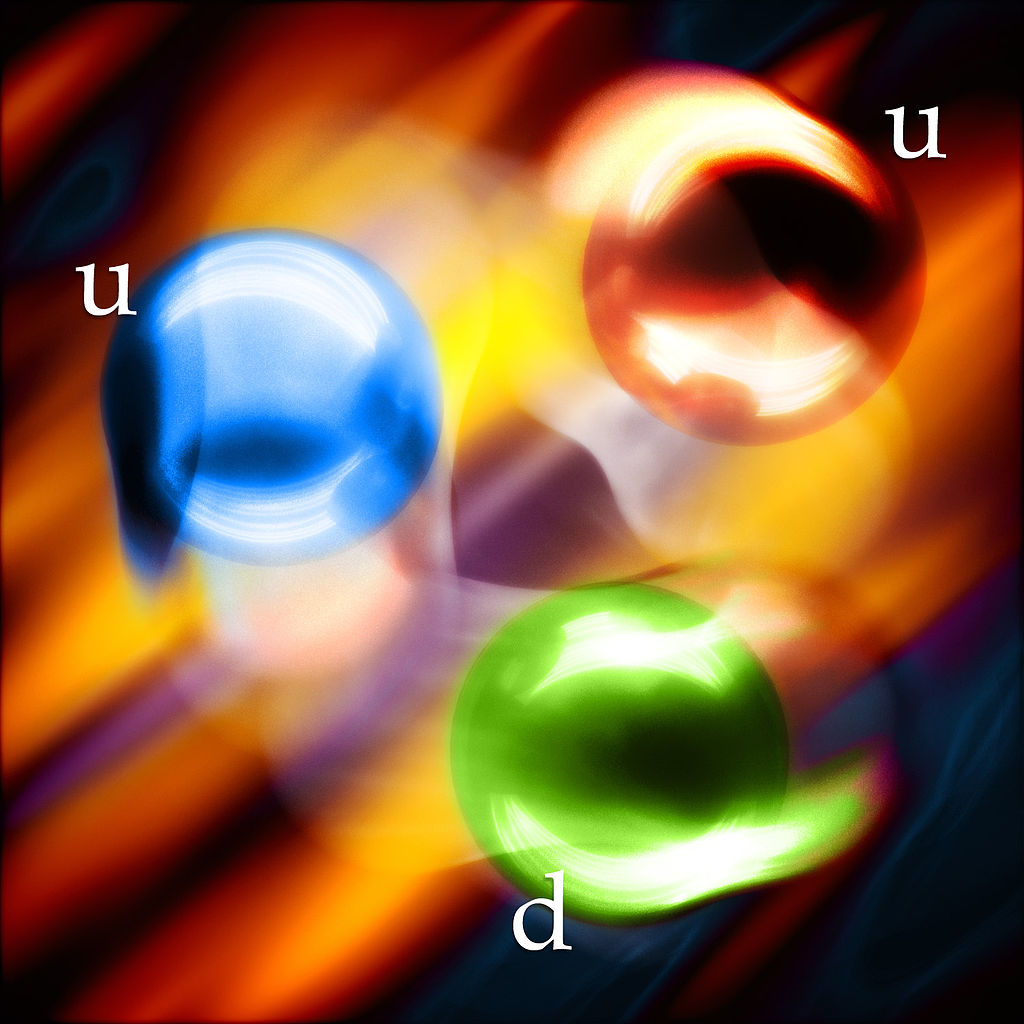

A proton is made of 2 up quarks and 1 down quark. A neutron is made of 1 up quark and 2 down quarks. So, quarks make up both protons and neutrons.

(Amazingly, if a quark can “flip” from down to up, a neutron will turn into a proton. This increases the charge of an atom’s nucleus—which can change the atom’s chemical properties completely! This is partially responsible for nuclear decay and radioactivity!)

> Also interesting: Considering all the nuclear waste, why is nuclear power considered clean?

An electron is the smallest particle

But an electron is not a hadron. It is not made of quarks. The Standard Model says that an electron is a fundamental particle.

We don’t know how big an electron is. Er, rather, how small. Trying to measure its size is somewhat problematic. If an electron has some kind of size, it’s smaller than our ability to meaningfully measure it.

Quarks. Well, the problem with trying to tell you the size of a quark is that quarks are very shy and they don’t like to be alone. They always like to be with other quarks, something called “quark confinement”.

Quarks are always bound to other quarks—usually as triplets, but sometimes pairs. (Other combinations are possible.) One of the fundamental forces of the universe—the strong force—becomes very obvious to quarks. It’s like a kind of “quark glue” that tries to keep quarks always clumped together. Except, unlike gravity, the more you try to pull quarks apart, the greater the strong force they exert to remain bound together. Things get very strange at very small scales.

Because we can’t get common quarks isolated, it’s very hard to tell you the size of a single quark. And, we don’t have a good idea of what “size” means.

In both cases, we often treat quarks and electrons as existing at a single point. Instead, particles spread themselves out in space in a probabilistic way.

Electrons are (smaller in terms of mass) than quarks

However, in terms of mass (er, mass-energy), the electron is lighter than the smallest quark.

So, if you care about the mass-energy of a particle, quarks are not the “smallest part of an element.” Electrons are teeny-tiny things. Why, the very word “lepton” means something close to “thin particle”.